Knowledge, Understanding, and Quarterbacks

The only path to true understanding is through falsifiable predictions.

It’s so easy to mistake facts and the accompanying words we’ve memorized to convey them as understanding. The real test for comprehension, though, is predictive power.

I’ve believed for a long time that things we say we know are not only mostly false, but even when correct, they’re still actually things we don’t understand. When I think about what I “know,” I realize I actually understand almost none of it.

Why does my television turn on and play when I click the power button on my remote control? I can say generic things I’ve been told.

“The controller sends a code to the TV at a specific frequency, flipping a transistor to energize a logic board. The TV receives code from satellites at the speed of light that details which exact photons to send to specific pixels at exact times to create a motion image I understand.”

I think this is factually accurate, and yet I don’t understand a single word of it. I really have no idea how this works, at all. Like none of it, and it’s probably fair to guess you don’t either.

Seriously, how does a TV do that? And if you know a whole lot about TVs, I’m sure you can explain it in a lot more detail than I can, but my guess is you’re just better at remembering the exact combination of words to use to make it seem like you understand, but you don’t really understand.

And it seems to me most knowledge–basically all of it–is just remembering how to utter syllables in such a way that it resonates with someone else who has heard a similar combination of syllables in the past.

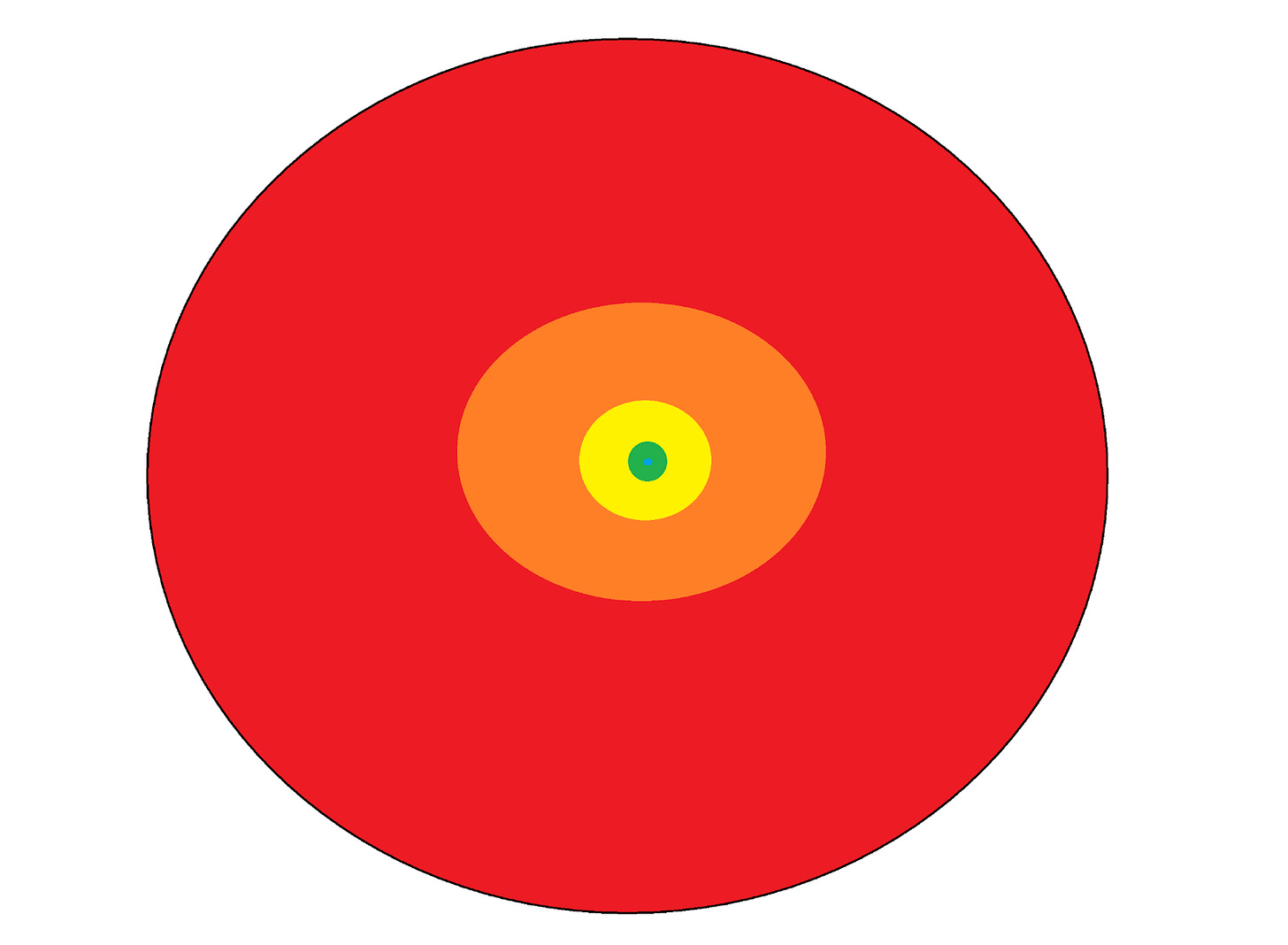

And so my current theory of knowledge can be represented by this wonderful Paint drawing I just created…

…where the different colors represent the following:

Red: Things you “know” that are factually wrong

Orange: Things you “know” that are factually correct but misleading or useless

Yellow: Things you “know” that are factually correct, useful, but you don’t understand

Green: Things you superficially understand

Tiny Blue Dot You Probably Can’t Even See: Things you understand and can predict

Most of what you think you know is not even factually accurate. The easiest way to see this is true is to consider what you believed to be true, say, 10 years ago, and how little of it you still believe.

Most of what you know that’s factually accurate is misleading and often useless information. Polar bear skin is black. Who gives a shit?

And even that statement has different levels of “truthiness” to it. It’s factually accurate in that if we shave a polar bear down like Michael Phelps so he can swim faster, his skin would be a color we’d all use the word “black” to convey.

But from another view, the polar bear’s skin isn’t black at all. Color is a mind-dependent quality. There’s no trait inherent to the polar bear’s skin that’s black, but rather it just reflects light back to our eyes in such a way that our mind recognizes it as something that we’ve labeled “black” in the past.

And even in explaining that, I don’t actually know what the hell I’m talking about. I just know key phrases to say to evoke some imagery in your head that I’d like to.

Then we have facts that are true and useful, such as “fire heats up the pan on my stove,” that still mask ignorance of what’s actually going on.

Yeah, the pan heats up, but how does it do that? Of course I can say things like the fire emits energy and the heat molecules transfer this kinetic energy to the pan, and the electrons in metal are structured in such a way that they carry that heat energy uniformly across the pan to heat it. But again, I don’t actually know how that works. I’m just saying things I’ve heard in the past. Even the things we know to be true and useful, we don’t really understand.

So how do we get to true understanding? It’s certainly not by repeating memorized words.

In my view, the only way to demonstrate understanding is to make accurate predictions. That’s the hallmark of science–it’s how we prove theories to be true–and it’s how we demonstrate comprehension over observation.

And so in the progression of knowledge to understanding, I think it goes something like…

First you’re wrong;

then you’re technically right about something misleading/useless;

then you’re right about something useful but can’t explain why;

then you’re right and can retroactively explain why;

then you’re right and can predict what will happen in the future in that domain.

I’m going to leave you with my own progression through these steps with something I think we can agree everyone finds interesting: the hand size of NFL quarterbacks.

I used to believe being tall was a primary driver of NFL quarterback success, and to this day, I’d say most NFL analysts believe quarterbacks need to be tall to “see over the offensive line” to deliver the football. This doesn’t really make any logical sense for a variety of reasons, and if you talk to quarterbacks, they’ll tell you they throw through lanes rather than growing to like 10 feet tall and seeing over top of their linemen.

There is data that taller quarterbacks perform better, which is why this idea persists. But why is that the case? This is probably my favorite piece of information I uncovered in my years doing football analytics; for the most part, tall quarterbacks perform better not because they’re tall, but because being tall is correlated with something meaningful, which is having big hands. Large hands allow them to control and more accurately throw the football. You ever throw around a small NERF ball? I feel like fucking Dan Marino whipping those things around.

So my personal path from knowledge to understanding in this area was something like:

Quarterbacks need to be tall to see over the offensive line.

Tall quarterbacks do better than short ones.

Tall quarterbacks do better because they tend to have bigger hands.

Quarterbacks with bigger hands can better control and more accurately throw the football.

Short quarterbacks with big hands will outperform expectations, and tall ones with small hands will underperform.

In my case, the correlation between height and quarterback success does indeed break down when you adjust for hand size.

For example, second- and third-round quarterbacks Drew Brees and Russell Wilson found amazing success despite being very short by quarterback standards, due in large part to their 10.25-inch hands.

Meanwhile, first-rounders like Ryan Tannehill and Paxton Lynch were busts despite being tall, due to possessing the hands of a prepubescent girl. Lynch checked in at 6-7 with 9.25-inch hands, able to see completely over the offensive line while incapable of palming an apple.

You start with a wrong belief, observe things about the world, attempt to better understand why things are the way they are, and then test that belief with a falsifiable theory.

Until you’re able to consistently predict things about the future, you’re effectively just reciting memorized syllables.

Well done !

Hands of a prepubescent girl haha. Nice one.