The Secret to Success: Mimic Evolution

Why Nietzsche and Taleb have it right: we should learn from and mimic natural selection.

I love philosophy. I majored in philosophy and took it for every possible elective, partly because of how much I enjoyed studying it and partly because after majoring in biology for four days before quitting, I kind of knew I wasn’t going to have a normal career anyway. Philosophy’s marketing campaign should be “Eh, fuck it, I’ll just major in philosophy.” That’s how I got there, and it was one of the best decisions of my life. See: most decisions really don’t matter.

My favorite philosopher was and still is Friedrich Nietzsche, who gets a bad rap for being characterized as many things he wasn’t (and some he was). Nietzsche has a lot of parallels to Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who is my favorite living philosopher (one of those similarities is walking for long periods each day, which I highly recommend). I’m not putting Taleb on Nietzsche’s level—and I disagree with a lot from both of them—but to me, it’s doesn’t matter how much you get right as much as how useful/innovative/paradigm-shifting the things you do get right end up being; despite being kind of crazy people, no one has shifted my worldview more than Taleb and Nietzsche.

One of the themes inherent to both philosophers’ work is evolution, in slightly different ways. A 19th-century philosopher, Nietzsche was the first to really apply natural selection to ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, and basically everything about how we exist (despite harshly critiquing Darwin). Taleb more so employs human evolution as a basis for “what works”—the ultimate Lindy effect—and then draws principles from natural selection about how the world works and how best to operate.

If there is something in nature you don't understand, odds are it makes sense in a deeper way that is beyond your understanding. So there is a logic to natural things that is much superior to our own. Just as there is a dichotomy in law: 'innocent until proven guilty' as opposed to 'guilty until proven innocent', let me express my rule as follows: what Mother Nature does is rigorous until proven otherwise; what humans and science do is flawed until proven otherwise.

Taleb

I’m not sure how much my views have been shaped by these philosophers as opposed to me gravitating toward ideas naturally similar to mine, but I fundamentally believe in the power of both copying natural selection and applying the lessons it has for us in our everyday lives. It’s the ultimate selection bias; what’s left standing after millions of years is here because it works.

This isn’t a new concept; it already exists in fields like biomimicry—design that’s modeled after nature—and there are many examples of its pragmatic value. Velcro was created after someone noticed how burs stick to clothing. Climbing pads mimic gecko’s feet. Shock absorption is modeled after woodpecker beaks, architecture after termite mounds, and swimming suits after shark skin. Even materials designed for water absorption mimic the shell of the Stenocara beetle—a desert insect whose back is covered in small bumps and a hard wax that funnel limited water and condensation to the beetle’s mouth.

What we see today is the best of the best of the best because, if it weren’t, it wouldn’t be here. I’m sure there was a beetle out there at some point with a random gene mutation that caused it to funnel water to its asshole instead of its mouth. And now that beetle is dead.

What to Learn from Evolution

There are many reasons why we can look to natural selection for knowledge and insights, but I’m going to focus on what I believe are the most important lessons, along with how they can be applied to better yourself.

You can be dumb.

There is no guiding hand behind evolution; all the marvels of the natural world—the processing power of some human brains, the speed of Peregrine falcons, the complexity of mantis shrimp eyes (really, look it up)—has been accomplished without a single individual even being aware of the process.

You can be dumb and still find huge success, as long as you…

Perfect the trial-and-error cycle.

Evolution is more or less one giant system of trial-and-error. Nature changes, species adjust. Some traits live and some die off.

The key is that there’s a mechanism for the weakest traits and species to fizzle out. The harsh reality is that’s death. Survival of the fittest.

We see the same thing in some industries, which do a pretty decent job of mimicking evolution, mostly via competition. Taleb points to the restaurant business, which is fiercely competitive. Mostly, bad restaurants end up dying off—no one comes to eat—and only the strongest survive. The entire system gains from the process, and the food industry as a whole evolves fairly rapidly.

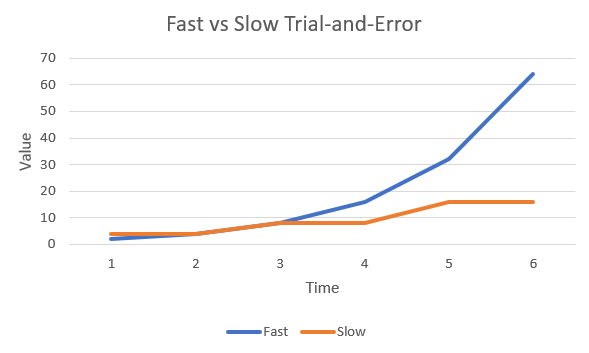

The faster and more efficient you can make this trial-and-error cycle, whether it’s in your personal life or your business life, the quicker you will find success. Your starting point for truth is way less important than your process for refining and improving your beliefs, especially when you get away from a static worldview and begin to (appropriately) see it dynamically.

Over time, differences in the speed at which you can process information and adapt become exponentially more important than where you begin.

In this very hypothetical example, the fast learner begins with half as much knowledge/value as the slow learner, but doubles it every cycle, compared to every other cycle for the slow learner. You can see how the difference in the velocity of the learning curve plays out over time.

The best way to speed up your learning curve: be extreme.

Don’t suppress chaos.

Natural selection is what Taleb would term “antifragile”—the opposite of fragile—because not only is it not harmed by chaos, it benefits from it. A species can change for the better fairly quickly in evolutionary terms from a single random genetic mutation.

Even natural disasters are positives for most species as a whole, assuming they’re not entirely killed off, because they end up coming back stronger and more prepared. Humans, too, are hopefully more prepared for the next pandemic; COVID has been devastatingly brutal, but “good” and “bad” are designations that often change based on your time horizon. What’s bad in a static environment can often be one of the most beneficial things when viewed long-term.

Failure saves lives. In the airline industry, every time a plane crashes the probability of the next crash is lowered by that. So these people died, but we have effectively improved the safety of the system, and nothing failed in vain.

Taleb

By embracing chaos in all aspects of life, you’re set up for more sustainable long-term success. That’s one reason I tweeted this:

Not all jobs are the same and every person is different; there’s no one-size-fits-all plan for everyone. In fact, most people are probably best off in the employee role.

Generally speaking, though, one of the biggest misconceptions about being a salaried employee is that it’s safer than something like an independent contractor. Being a contractor isn’t always a great solution—it’s not feasible in some areas and takes a long time to build a customer base—but who do you think is more susceptible to a sharp change in income: someone making $70,000 a year from one employer or someone earning the same amount from eight clients in two different niches? The latter is more volatile, but the former is riskier.

Evolution embraces chaos, and in exchange eventually delivers the best results. Without that volatility, there could be no progress.

Nature builds things that are antifragile. In the case of evolution, nature uses disorder to grow stronger. Occasional starvation or going to the gym also makes you stronger, because you subject your body to stressors and gain from them.

Taleb

Don’t deprive yourself of life’s shocks; they’re what allow for your personal evolution.

Think long.

Evolution needs time to operate. This is a characteristic of things that like chaos; they love time. The more time, the better, which runs in opposition to most things, which eventually break down over time.

Many people are doing things—whether professionally or personally—that, unbeknownst to them, will not survive over time; they’re eventually going to go busto, as we say in the gambling world.

If we’re being honest, most people can’t even calculate expected value in static environments. A much smaller percentage know how to do it over time, choosing what’s optimal in arenas in which the first order of business should be eliminating risk of ruin, i.e. “not dying.”

Natural selection does this better than any business in the world; it’s built into the system. Species maximize their chances of survival as a whole above all else. Survive, then optimize.

Build systems that embrace volatility and are meant to survive and improve with time.

Humans naturally behave in predictably sub-optimal ways.

Because we are conditioned to survive and reproduce, there are certain things we do or ways in which we think that are beneficial for the survival of the species but really crappy for being a successful and happy human.

As an example, I experience extreme nervousness in certain social situations in which I need to talk in front of a group of people. I could be the most knowledgeable person on a topic by a large margin, and I still feel nervous. Why? It makes no sense. It doesn’t help me today—in fact, it’s a detriment—and yet no matter what I try, I cannot shake the feeling.

Evolution takes time, and we’re built for our species of many generations ago to survive. But we’re not the same as many generations ago, and some of the psychological tools we’ve evolved—like feeling nervousness in situations we perceive as high-leverage to survival—are no longer very useful.

We’re in a constant battle between our reasoning selves and our emotions. The latter have their place—specifically when doing what’s best right now, like running away from that angry-ass-looking lion over there, is also best long-term—but our ability to reason is more imperative today. In a world in which survival is nearly guaranteed for most, the best decision is usually the one that’s best long-term; calculating that, however, takes logic over emotions.

The thing is, most people aren’t doing this properly. They’re acting extremely emotionally all the time without even really realizing it, letting their feelings of the way the world is or should be overrule their logical selves, and these psychological biases form a pretty predictable and exploitable pattern.

Practical Consequences in Everyday Life

So those are sort of my semi-philosophical/semi-pragmatic implications for what it means to model our lives after evolution. Using those principles as a foundation, I’m going to do my best to draw what I believe are direct (and pragmatic) consequences for shaping how we live.

You don’t always need more data. Usually, you need less.

Do you think birds are sitting up there in their trees, working on aerodynamics and calculating the optimal wing shape they’d like to achieve in 10 generations? Crunching the numbers to figure out the best altitude at which to fly to conserve maximum energy?

No, they just sit there being dumb birds and doing dumb bird things. When they do move, they often fly into windows and die. It’s estimated that up to nearly 1 billion birds die colliding with windows in the United States each year. I’m going to go ahead and call bullshit on that one by the way. That’s like three bird deaths per person. It’s 10% of the entire bird population. You’re telling me that in any given year, a bird has a 10% chance of flying into a fucking window and dropping dead? I don’t know man, that seems outrageous.

The point is that birds are dumb and don’t use data, and yet they’re crushing it (literally) because the process above them is iterative. And the faster the cycle, the more they can change in a given time period. The faster you can make your own trial-and-error knowledge cycle—action, feedback, change, another action—the less you need data.

I’m saying this as someone who has written many books on a data-driven process to gambling. Math is absolutely essential to a logical decision-making process. But it almost always should be used to inform the process, not make the individual decisions. Even random actions at rapid pace are better than deliberate ones as long as you’re implementing data to improve the process by which you take future actions.

The more data we have, the more likely we are to drown in it.

Taleb

The best ideas and actions must win.

An essential part of evolving as a person is to let good ideas live on and adapt and bad ideas die. The key is to drop your ego. Trust me, you have one, and it’s probably larger than you think. Your ego doesn’t always result in being cocky publicly; it can just mean not being honest with yourself about when you’re wrong.

A useful practice: write down one thing you were right and wrong about each day. This becomes quite easy if you make small bets on your beliefs. When you gamble, you’re not only forced to refine your probabilistic thinking about the world (and do it in a way that’s totally honest with yourself as, if you’re wrong, you lose money), but you’re also forced to confront just how often your beliefs are inaccurate.

For so long, people have used upside for motivation. Companies give employees small bonuses if they reach X goals. People make internal deals with themselves: “If I reach this weight, I’ll go on a trip.” But motivation is stronger from downside. “Oh, if I don’t learn what the fuck I’m doing I’ll lose my money?” Okay, let’s get to work.

The biggest hurdle I see in terms of self-improvement is people not understanding they aren’t being intellectually honest with the most important person necessary: themselves. Taking on downside via gambling forces honesty like nothing else I’ve experienced.

You might think you have yourself all figured out, but if you really want to know what you believe, bet on it. Chances are you aren’t being as honest with yourself as you think.

If you run a business, you should set up the same concept as a meritocracy. If you are searching for a company for which to work, you should look for one that rewards greatness and not seniority. This is actually quite rare.

Again, this requires setting aside your ego. Most people don’t want to give up control or aren’t okay with admitting they’re wrong. Let me tell you right now, and I believe this strongly: if the head of a company is not okay being called out by the “lowest” person in the organization, and if there is no process by which the “boss” can and will admit they’re wrong and concede to the best idea when it’s appropriate, the company cannot possibly function at the highest level.

The best leaders lead without anyone knowing they’re leading.

The higher we soar, the smaller we appear to those who cannot fly.

Nietzsche

I don’t mean to get too Taoist (secretly I do), but it’s true. The best leaders are “one of the gang.” And not in some like pseudo- sense in which they pretend to listen to those they’re leading but then go back to their throne; I mean truly on the same level, and then they sort of take all the information around them and just guide the ship without people really even recognizing what’s going on.

The best leaders are those the people hardly know exist.

The next best is a leader who is loved and praised.

Next comes the one who is feared.

The worst one is the leader that is despised.

The best leaders value their words, and use them sparingly.

When she has accomplished her task, the people say, "Amazing: we did it, all by ourselves!Lao Tzu

Leaders aren’t bosses who tell people what to do. Leaders are the guiding force behind a collective movement toward truth and usefulness—toward the most appropriate ideas, decisions, and actions in any given situation, regardless of the source.

“The best fighter is never angry.”

- Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

“The best leader is never bossy.”

- Jonathan Bales, This Article

Don’t accept fragility.

I mentioned why I believe the typical career—salaried employee—often represents a confusion of risk and volatility. It’s absolutely fine for you to trade in EV for smooth income—we trade in EV for limited downside in the form of health insurance, for example—but my hunch is that many believe they’re limiting their risk with a salaried job, not just their volatility.

As much as possible, you should diversify income streams if it’s an option. The internet has made that more of a possibility than many realize.

Of course, the Catch-22 is that most people rely on their salary and just fully jumping into a freelance role or starting a business isn’t really an option. So do it over time. If you’re a writer, start looking for occasional freelance writing work in your spare time. If you’re an engineer, find a one-off coding project. Or do it when you’re “at work.” Most people aren’t actually working all day while they’re “working all day.”

At the level of the business, I’m a big believer in building companies as an umbrella of various verticals—joined by a common theme but really separate in distinct ways. Each vertical should be run as if it’s its own business—one that is very specific and many would see as almost too “niche.” What this does is unites each vertical (if a customer finds one they can find the others), allows the company to benefit from the 80-20 rule (if you want to grow big, first grow small), and localizes failure (the repercussions of launching a new product or concept that stinks don’t extend throughout the entirety of the company).

Regarding the last point, the equivalent in evolutionary terms is gene diversity. Species evolve to not be heterogenous, which eliminates or reduces correlated points of failure. This should be sort of obvious—don’t build a house of cards—but why does it seem like so many people don’t extend this simple idea to their personal and professional lives?

I’ve always found it odd when companies acquire smaller competitors and then try to roll them up into one. I much prefer the idea of a conglomerate of small, focused companies for “hardcore” power users. My 60-second Paint representation of this idea is something like this:

On the top, you have a sort of web of companies or verticals or concepts that are interconnected; this has some benefits, but the failure of one brings down others. On the bottom, you have a very broad umbrella concept up top, with very specific verticals underneath. This “broad via the collection of specific/separate” idea is far less fragile, easier to scale, and I believe probably possesses more long-term upside. What makes it such is that the diversity within each vertical is maintained by their separation. This localizes failure much like gene diversity does for species following environmental changes.

On the individual level, having a single source of income is the equivalent to having no diversity in a gene pool; there’s a single point of failure. Varied sources of income—and, all else equal, those that aren’t correlated—reduce fragility and maximize the odds of staying in the game.

Antifragility through diversity. The ultimate example of this idea: the founding of the United States of America.

Globalization has created this interlocking fragility. At no time in the history of the universe has the cancellation of a Christmas order in New York meant layoffs in China.

Taleb

Some other ways to remove fragility in various aspects of life:

1. Avoid risk of ruin.

You should take on all kinds of risk when there’s nothing to lose. If you have $5,000 to your name, it doesn’t really matter if you go busto. If you have $500,000, there’s more to lose and thus your first aim—before any optimization—should be staying in the game.

2. Admit how little you know.

Overconfidence is fragility. It will eventually blow up. Cocky people look like they’re winning more frequently than others. And they might be winning more battles. But if life is a war that has no ending, they will eventually blow up and lose.

As Vince Lombardi said, “We didn’t lose, we just ran out of time.” If your time horizon is “forever,” then anything that is fragile will always lose, with 100% certainty, and anything that’s antifragile will always improve, with 100% certainty. Overconfidence looks good temporarily, but always loses over time.

Convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies.

Nietzsche

We all have beliefs we hold right now about which we are way, way too confident. I once did magic for girls in bars because I swore it would help me get laid. Actually, I still kind of stand by that; people love magic! No one really know this, but I was really awesome at street magic. Anything that David Blaine could do with cards, I could do. He did it for massive fame and wealth and I did it to once go on a few dates with a girl named Emily who doesn’t like Mexican food and probably should have just told me about that before I took her to La Placita, but it’s all good Emily we can still get dessert or something after I eat my enchilada if you’re down and also is THIS your card?

I bet on Trump to win the presidency in 2016 at ridiculous odds because I thought people were overestimating what they thought they knew about politics and his relative odds of winning. But the thing is that I know nothing about politics. Like really, I know nothing. So one thing I think I did well this election was just shut up. I had a small position on the outcome, but I had next to no confidence in it and so rather than blab about winning last time and delude myself into thinking I know what I’m doing, I didn’t really say a word because I truly don’t have anything to say about it (from a probability standpoint). Actually, that’s not entirely true; I did bet a small amount on Bloomberg, gotta admit. That, my friends, is what we’d call a blunder.

The point is that sometimes, the best thing you can do is just not speak. Like, probably most times.

You have to admit you don’t know everything. Some people stink at that. But an even rarer skill is admitting that, statistically, many things you think you know right now are just wrong. And so you have to have a certain humility to really avoid fragility in most aspects of life. The easiest way I’ve found to do that is look back on how you were years ago—what you believed and how you acted—because that’s usually pretty damn embarrassing. If it isn’t, I’d argue you’re probably not growing enough as a person. If life were a game of regretting as much as possible in the future, I’d be in the Olympics.

Now, how do you go about admitting how little you know while still maintaining a healthy confidence in yourself? Rome wasn’t built in a day. I’m working on it.

No victor believes in chance.

Nietzsche

Practice constantly dealing with uncertainty, risk, chaos.

I wrote about how to deal with uncertainty. You cannot maximize EV, income, even happiness long-term until you’re comfortable dealing with uncertainty. Again, the easiest way to become comfortable: gamble. Bet with friends, think in probabilities, put downside on your beliefs—just constantly make predictions about the future.

I’ve talked about the benefits of this many times, but one inevitable (and overlooked) outcome of doing it that I haven’t really mentioned is that you get better at seeing obstacles as opportunities.

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Nietzsche

When a natural disaster hits an island and decimates a species’ population, it’s difficult to not view that as a negative event. But if the species survives, they’ll usually come back stronger over time. Natural selection teaches us nothing is inherently good or bad; it’s relative to your viewpoint and time horizon.

You can embrace this idea in your life, too. When “bad” things happen, they’re usually seen that way on a relative basis and with a static point of view. But they don’t need to be that way. Species don’t sulk in the shitty circumstances they’re dealt; they just adapt.

I was just watching a video of pro poker player Phil Ivey describing a hand he lost to Chris Moneymaker in the early-2000s. Ivey was a huge favorite but lost the hand. He said he didn’t have much money at that point—which seems like a small exaggeration but who knows—and he was robbed of potentially millions of dollars. In that moment, it was a hugely negative outcome for Ivey.

Zoom out, though, and Moneymaker went on to win the tournament—an event most label as the start of the poker boom. Without it, Ivey—who went on to accrue incredible wealth through poker—might have had a much different story. Long-term, losing that hand might have been the best thing to happen to Ivey’s poker career.

I’ve found it helpful in my personal and business lives to view everything that happens simply as information. Whether it is “good” or “bad” is completely relative. It has really helped me to remind myself that when something looks like an obstacle, that’s because I’m thinking too narrowly; expand outward and it often resembles an opportunity—a catalyst for positive change that could not be possible without that short-term hardship.

Of course, doing this in the moment is really damn hard. So just practice and work to improve that mindset over time. I still have a long way to go, but I’m better than I used to be.

Optimize for five years.

Charlie Munger’s advice to those looking to acquire wealth is to do everything possible to get to a savings of $100,000. Work multiple jobs, spend as little as possible, and do anything you can to create that buffer.

I was on the Hxro Labs podcast discussing a similar idea. I’m not a big believer in getting rich via saving—you get rich by finding ways to make more money—but in the beginning, it’s pivotal for you to build up a base via any means necessary.

This is sort of my “long view” of wealth, which is that what you do early (that I think is generally sub-optimal)—save money—is actually very optimal with a longer view because the sooner you acquire some sort of base, the sooner you can make real money. Actually, for certain people, I think even small -EV gambles early on can be smart if you do +EV things later just because it’s so important to get money early. I’m sure you’ve seen the graphs of your retirement if you invest $X from age 25 instead of 35. Due to compounding returns, it makes sense to do whatever you can to get that early stash. Or maybe that’s just me rationalizing why I kept firing daily fantasy golf on DraftKings despite maybe the worst ever ROI the site has ever seen on the sport.

This sort of long-term EV calculation should be applied to other aspects of life. Exercise is always a great example. When you work out, you put your body through temporary stress for delayed returns that outweigh the pain. If something that sucks as much ass as exercising can transform from “this is the dumbest possible use of my time today” to “there’s maybe nothing better I can do for myself long-term,” then think about all the other benefits you’re overlooking by not thinking far enough into the future about what’s optimal.

Use emotions as a trigger to think logically.

I got this advice from Ray Dalio in his book Principles. It’s an extension of an idea we have in gambling—one Brandon Adams discusses in his book Personal Organization for Degenerates—to avoid consequential actions when on tilt. Basically, when you recognize emotional behavior in yourself, just stop doing things that matter.

Dalio takes it one step further, arguing you should condition yourself to use emotions as a trigger for rational thinking. When you find yourself in an argument with someone and you really just want to do what comes naturally and scream “Dude just shut the FUCK up!”…use that feeling as a reminder to take a step back and think logically. And then, politely and in a soothing voice, calmly state “Pardon me, kind sir, but if it’s not too much trouble, would you mind doing me the favor of just shutting the fuck up?” I don’t know why but when I say that out loud it’s in a British accent.

There’s a time and place for emotional thinking, but just because it’s necessary for the survival of our species doesn’t mean it has a place in all or even most of your everyday decisions and interactions. I might be in the minority with this view, but I believe emotions are pretty much always a detriment to sound decision-making and they’ll slow down your trial-and-error cycle if you don’t find a way to get around them.

Think one level above yourself.

Your brain is in a constant battle between the logical and the emotional—what you can reason and what your animal self naturally feels—and what you’re doing when you overcome those emotions is basically thinking outside of yourself on a higher level to make better choices. Whether or not that represents some form of free will I don’t know, but if we think of freedom as existing on a spectrum, then this would be at a higher end of that range than just giving in to your feelings. You won’t ever stop feeling these natural urges, but you can recognize them in yourself and make decisions that minimize their impact. That’s not to say your instincts don’t matter—they most certainly do—but rather that they shouldn’t be driven primarily by emotions.

There are two main reasons I think you should work to think a level above your natural self. The first is that, since almost everyone else is succumbing to their feelings, you’re going to naturally be contrarian—and thus secure the greatest payoffs—by thinking rationally at all times. It’s not only optimal in a vacuum, but also optimal in terms of game theory—a natural way to exploit the masses. This is surprisingly easy to do for groups; an individual might act unpredictably, but humans as a whole tend to have the same sorts of illogical thoughts, suffer from the same psychological biases, and act in the same irrational ways.

I spent a lot of time over my life studying these psychological biases. Even just being aware of the types of ways in which your brain is hardwired to deceive you can have a meaningful impact on your ability to recognize irrationality in yourself—and trust me, it exists in a multitude of ways—so you can make better choices in spite of your natural biases.

Second, it’s antifragile. Humans are fragile at the individual level, but that fragility creates antifragility at the species level in the same way the restaurant business is antifragile because each individual restaurant is fragile. Similarly, your natural ideas and feelings are fragile, but that can create antifragility if properly leveraged to improve your higher-level self. Your process of thought and decision-making can transform into one that improves exponentially over time if you recognize your limitations, overcome your biases, and make decisions outside of what your inner self is naturally telling you to do. The effects of improving that process are compounding. Basically, try to become the Amazon.com of humans.

And if none of this works, might I suggest spending countless hours learning street magic?

The most spiritual men, as the strongest, find their happiness where others would find their destruction: in the labyrinth, in hardness against themselves and others, in experiments. Their joy is self-conquest: asceticism becomes in them nature, need, and instinct. Difficult tasks are a privilege to them; to play with burdens that crush others, a recreation.

Nietzsche