How to Improve Your Decisions, Immediately (And Why *Almost* Nothing Matters)

The key to making better decisions is to realize that most of them don't matter all that much.

A few weeks ago, I tweeted this:

I thought about this a lot since then. Why do I not care or have no opinion on almost everything? Why do I think most decisions really don’t matter very much? Rather than take a good, hard look at myself to identify any underlying issues with the way in which I see the world, I figured I’d instead try to use reason and logic to explain away my potential weaknesses and justify my character flaws so they never actually need to be addressed.

So here is my attempt to explain why I really do believe most things don’t matter and you shouldn’t actually care about them—and specifically how that relates to decision-making.

Many of life’s decisions, and maybe most, don’t matter. The majority of the information people assess doesn’t matter, but also the choice that’s made itself doesn’t matter. I mean this in the typical way you might expect, which is just that the consequences of the decisions are trivial. Should you have sausage or bacon for breakfast? Who cares?

But I also mean it in another important way, too, which is that many decisions are actually coin flips or pretty close to coin flips, and it just doesn’t matter what you pick. This can be the case with small decisions, like which shoes you should wear on a date, but also with very consequential ones, like where to go to college. Yes, which college you choose probably matters a lot, but once you’ve put a certain amount of time into selecting a school, there are diminishing returns on putting in more effort. If two options seem equal, they probably are.

That doesn’t mean the results will be the same. Rather, the EV (expected value, or probability times payoffs) of the decision is roughly the same on both sides at the time the decision is made, and it’d be dumb to keep analyzing every aspect of the decision in the same way you wouldn’t over-analyze a coin flip. You could have $1 million riding on a coin flip—very consequential results—and the decision to choose heads or tails still doesn’t matter.

You can only know so much before making a choice; this uncertainty in decision-making and the subsequent randomness in life—of which I think there is more than even most people who talk about randomness believe—means we’re probably not as good at making individual decisions as we think.

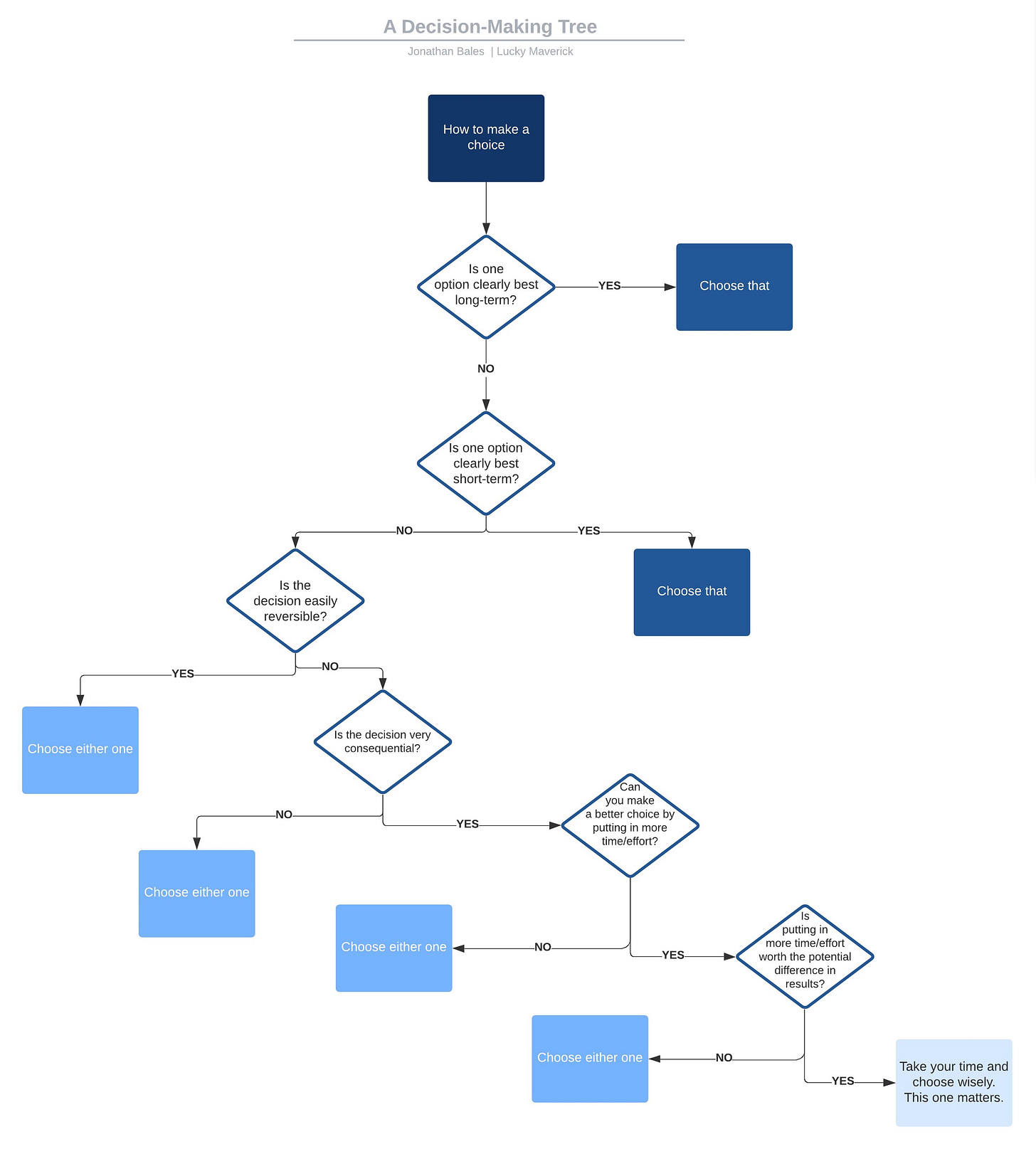

But we can still improve mightily in improving the overall outcomes of our decisions! How can this be? Before diving in, I made a flow chart I want to share. Guys, if you recall, I’m not the best with design. I have another article I’m working on, and this is a graphic I made.

I actually took the time to make this. This is something that I—an adult, with working eyes—created with an intent to show others. And I was planning to ask you all to pay me for it. What a world.

So when I present the following graphic, please know I’m so proud of it that I’m serious when I ask you to join my effort to have it shown in the MoMA.

What an absolutely gorgeous piece of modern art. A simply stunning take on a very boring flow chart. It’s also monochromatic, which is nice. And I am trying to be humble—really, I am—but it only took me eight hours to make. You’re not paying for that time, you’re paying for all the hours I put into developing my Microsoft Paint skills to even get to the point to knock this out in a full day. Actually, you’re not paying me at all. This is the worst ROI of all-time; what was I thinking?

The reason I made this is because I was thinking about how I sort of reason through decisions, and why that might lead me to not care about a lot of things. That’s not to say this decision tree is the right way to think; I was just trying to consider how I come to make decisions.

It was actually a very useful (and difficult) exercise to create this, because it forced me to think concretely about an abstract process. It isn’t like I have some formal process for making choices. This is just a visual representation—or as close as I could get—of something tacit. Read: why tacit knowledge is so important.

To summarize the graphic:

1 Is one option clearly best long-term?

If yes, choose that. If no…

2 Is one option clearly best short-term?

If yes, choose that. If no…

3 Is the decision easily reversible?

If yes, just pick something. If no…

4 Is the decision very consequential?

If no, just pick something. If yes…

5 Can you make a better choice by putting in more time?

If no, just pick something. If yes…

6 Is putting in more time worth the potential difference in results?

If no, just pick something. If yes…

Take your time and choose wisely. This one matters.

This of course isn’t a rigid framework. I don’t always make the best long-term decisions, for example. These are just heuristics of how I think I usually sort through information, but sometimes the order might be reversed or I value happiness right now over doing the best thing long-term or I might have a strong gut feeling about something that leads me away from what I’d “normally” do or what might be deemed mathematically correct on paper.

Still, I believe that most of the time, the correct solution is “pick a card, any card.” Here’s why…

How I Make Decisions: My Heuristics

As best as I can explain my thought process, this is how I sort through information and make choices—my general rules-of-thumb. This is probably sub-optimal, but it’s close-ish to how (I think) I do things. In walking through this, it should become clear why I believe most stuff doesn’t matter.

They say don’t sweat the small stuff. This is true. But don’t sweat most of the big stuff, either.

1. If one choice is clearly the best long-term, pick that.

I talk about the value of long-term thinking all the time. It’s the basis for much of my reasoning behind working for free, and I covered it in the About section of Lucky Maverick.

In all facets of life, the most successful people are those who think long-term. There are a variety of names for it.

Dynamic thinking.

Second- and third-order effects.

Geometric returns.

Compound interest.

In my world, we’d say EV changes when you extend your time horizon. That is, the things that are “optimal” change based on the time period for which you’re optimizing. A simple example would be exercising, which we know has more long-term value than almost anything, but if you’re trying to optimize your day, you might avoid doing things like working out or eating healthy because, you know, they suck ass.

Usually, the things that are hardest now are the most +EV long-term. When unsure of what to do, make the decision that is best for the version of you that exists five years from now. This is true for your money, job, health, even how you treat people. If you’re ever undecided on an ethical decision, extend your time horizon; what’s “right” and what’s best for you tend to align. As one of my favorite thinkers Naval has said, “Being selfless is long-term greedy.”

Even the math on decisions like what to eat or how to work out changes with a slight shift in time horizon. If you’re trying to maximize calories burned while working out, for example, you might favor more cardio-centric exercises, whereas lifting weights keeps your metabolism up for a longer period of time and builds a muscular base for compounding returns, i.e. jogging helps you burn calories now, while resistance exercise allows your body to become more efficient at burning future calories. For long-term health, the last thing you should worry about is day-to-day fluctuations in weight, which are mostly the result of how much water you’re retaining at any given time.

Some choices have far superior long-term EV, and it’s the single most overlooked component of decision-making. You should be at least considering long-term effects with almost every important choice you make.

Unsure if you want to go out and party with friends or stay in? Don’t go. One has clearly superior compounding effects. Let me be clear this doesn’t mean you should never party or do anything that offers primarily short-term EV. Far from it. I probably make the “bad” long-term choice more than most of my friends, in fact. I am a degenerate gambler, after all. But I do the fun stuff when it’s clearly the best option in my mind. When it’s not or I’m unsure, I just think about what the version of me at some point in the future would want.

If you do nothing but focus on the very first part of this flow chart, I think you have a sizeable edge in most areas, for what it’s worth. Most people jump to #2 because they don’t know how to delay gratification—or they misinterpret data—and it creates larger future problems down the road.

2. If one choice is clearly the best short-term, pick that.

If your options seem roughly equal in terms of long-term EV, then do the one that’s best short term. Duh. This is pretty straightforward, but of course most difficult decisions aren’t obviously better in these areas, which is when we make our money.

3. If the decision is easily reversible, just pick a side and go.

When the consequences of a wrong decision are minimal, you should move with speed. This is the biggest way to improve decision-making, in my view: make more choices and quickly iterate upon them. You don’t need to be highly accurate with every decision if you’re allowed to evolve, and with almost every choice, you can.

It doesn’t matter where you start if you have an iterative process of thought evolution. Bad choices can become good ones very quickly if you can act fast and just deal with the consequences, then make small improvements along the way.

In James Clear’s book Atomic Habits, he writes:

Imagine you are flying from Los Angeles to New York City. If a pilot leaving from LAX adjusts the heading just 3.5 degrees south, you will land in Washington D.C., instead of New York. Such a small change is barely noticeable at takeoff—the nose of the airplane moves just a few feet—but when magnified across the entire United States, you end up hundreds of miles apart.

Very small changes can have profound impacts over long time horizons. Many decisions—and the most vital for acquiring wealth, in my view—aren’t made in static environments.

By focusing on choices as existing dynamically, it increases the value of trial-and-error. That is, when you can iterate to “change” the EV of a decision repeatedly over time, it decreases the importance of prior choices.

This should be obvious in the airplane example: would you rather be on a cross-country flight with a pilot who spends countless hours attempting to calibrate the most precise takeoff angle but can’t make adjustments along the way, or one who just sort of takes off in the general direction of New York but can make unlimited adjustments? Uh, yeah, the second one.

Does the takeoff have a giant impact on where you end up? Only if there’s no iteration along the way. For most of life’s choices, you get to make small changes—you have the opportunity to learn via trial-and-error—and that’s far superior to wasting time.

As an example, let’s say every choice you make in a given period takes 10 minutes and comes with a 50% probability of success. Now let’s say you can improve those odds to 75% with 10 more minutes of work (with the payoffs of both choices unaffected). Should you do it? Well, assuming you’re just trying to maximize EV, no, you shouldn’t. Firing 100 shots at a coin flip results in 50 wins, on average, meaning if you’re taking only half as many shots, you’d need to improve your odds of success to 100% to generate the same EV. I’ve simplified this for the sake of argument, but you get the idea; most decisions aren’t made in static environments and there’s an opportunity cost to everything you do, so very often you’re better off just moving quickly with “guesses” as opposed to making more precise predictions. But to do that, you have to be okay with letting go of control and knowing the probabilities will work out in your favor in the long run.

The key here is that the decision is reversible (almost all are). If only one option is reversible and otherwise equal to the others, choose the one that offers optionality. If the choice as a whole is reversible, just make a fast choice—no matter what it is—and move on.

This is the process of human evolution; there’s no master plan, no intelligence guiding the process. It just works because of trial-and-error. The key for the evolution of a species is that valuable traits are favored over ones that don’t aid survival; the key for thought evolution is that bad ideas (and decisions) are allowed to die off, and the good ones survive.

Thus, my grand thesis for this article is basically this: you’ll make the best decisions by improving the practice by which you select which of your ideas “survive,” and by speeding up the trial-and-error learning curve, i.e. what you choose is not as important as how you choose (the process) and how quickly you choose (the speed of the entire cycle, from the birth of a shitty idea to its death).

4. If a decision is of little consequence, just pick a side and go.

This is obvious, but I’d also propose that if you really think about what is important to you and what makes you happy in life, you realize many decisions are of little consequence. You can free yourself of so much stress and worry just by letting go of things that don’t fundamentally matter. Worry about the few consequential decisions that will have an actual impact on your long-term happiness and that of those around you.

5. If you can’t significantly improve the odds of making a better choice with more effort, just pick a side and go.

There are diminishing returns to putting in more effort on each decision. Like I said, there’s lot of randomness in the world, and there’s also a lot of uncertainty built into your ability to predict things. No matter how hard I try and how much work I put into a choice, there’s a theoretical limit on how well things can go for me.

In almost all cases, you should put in the time to make a good guess, do it fairly quickly, and move on.

6. If you can improve the odds of making a better choice but it isn’t worth the payoff, just pick a side and go.

Let’s say I want to bet on the Chiefs this weekend. Would I improve my chances of being on the right side by putting in more time studying the game? Of course. I could analyze every relevant piece of data, injury, news, etc. and I might improve by odds of winning a bet vs. the spread from 50% to let’s say 54% for this example, although it probably wouldn’t even be that high.

So putting in more time is worth something. But how much? At a 50% win rate and a -110 line (meaning I need to bet $110 to win $100 back), I’d have a -4.5% ROI on the week. At a 54% win rate, it would be a +3.1% ROI. That’s a sizeable difference, obviously.

Now let’s say I can get $10,000 on the game. That’s a $310 expectation at 3.1%. But I just said I put all week into this. At 40 hours, that’s $7.75 per hour. Even at a $50,000 bet, it’s $38.75 per hour, which is the equivalent of roughly $80,000 a year. However, I’d have to weigh that against 1) opportunities to make more money elsewhere, and 2) the risk I need to take on to make that money (that sort of risk for $80,000 a year is obviously unacceptable). On top of that, the expectation here is actually much lower because I could easily put in all kinds of time and find the line to be accurate, i.e. no bet.

Anyway, the point here is that just because you can improve a decision doesn’t mean you should, and in fact, you almost always should choose not to do so. It’s not that the decision doesn’t theoretically matter, but that the EV isn’t worth it. Many decisions are like this; it’s not that you can’t improve the decision, but that it shouldn’t be worth your time to do it.

Notice a theme here? Get close enough, make a solid educated guess, and move on. The reason I say the choice doesn’t matter is because…it doesn’t matter. What matters is speeding up and enhancing the process of improving upon your prior choices.

7. The only choices that matter are those that don’t have a clearly better option in terms of either long-term or short-term EV, aren’t easily reversible, have large consequences on your life, can be made better with more effort, and have a large enough payoff that putting in more effort makes mathematical sense.

So, almost none. The only mistake you can make with most choices is simply not making one: wasting time.

And that, my friends, is my logical breakdown of why “ah fuck it I’ll just flip a coin” is not only a completely reasonable decision-making process, but actually the optimal one, assuming you can flip the coin a lot and make small improvements along the way.

tl;dr

Nothing matters. Eat Arby’s.

The beginning remarks of this reminded me quite a bit of No Country for Old Men, where Anton used coin flips to determine his actions while simultaneously discussing how inconsequential each individual decision was to him - they just...were.

This was a very compelling article, made me think and gave me an updated perspective on a "simple" concept. That's all I can ask for on a Thursday morning!

Some interesting ideas, Jonathan, but I think especially regarding 5 & 6 you might be underestimating the possibility that the tails are non-linear & that therefore it may worth the additional research. I think that that is often where the most money made - https://www.honestbettingreviews.com/alex-bird-professional-gambler/ and https://www.theguardian.com/sport/1999/jun/02/cricket11 are example I've always liked but you could add Ed Thorp or some of the people who got the better of state lotteries in the U.S. Sure, these are seriously unusual examples and not the way to bet, but makes the point about possible non-linearity of the distribution of unknown outcomes.