How (Not) to Become an Entrepreneur

Learn from my failures. Keep firing lots of shots, quit fast when things don’t work, pour fuel on the winners, and remember that every mistake is an opportunity to learn and improve.

This is my second new Lucky Maverick article in the past two days after not posting since April 2, 2021’s instant classic “The Time I Sold Furbies for Money.”

I got a lot of great feedback from that article, such as “this really changed my understanding of the risk/reward spectrum,” “I’ve never thought about probability in that way,” and “this is literally the gayest thing I’ve ever read.”

That post was exactly 1,566 days ago, so set your calendars for October 15, 2029, when the next two Lucky Maverick articles will spontaneously drop back-to-back.

My Entrepreneurial Background

I started my first business when I was five. I stood on the sidewalk before kindergarten and did magic tricks for those passing by for 25 cents each. By “magic tricks” I mean “magic trick,” because I had just one.

I’d close my eyes and have someone pick a crayon, any crayon at all except that one please, then hand it to me behind my back. Incredibly, without moving the crayon from behind my back, I’d tell them what color they chose. Well it wasn’t that incredible, because I’d color the crayon onto my thumbnail and then slowly pass my hand over my forehead, checking for the color on my nail as I repeated the same line: “Boy it’s hot out here!”

Except I grew up outside of Philly and it typically wasn’t hot at all. It was like 40 degrees some days and I was pretending to sweat as I perfected my act. Anything for a quarter.

Throughout high school and college, I started a variety of businesses and hustles. They say you only learn from failure, which is why I’m so uniquely qualified to write this article; nearly everything I’ve ever tried has been a horrific defeat!

Ideas matter. Execution and iteration matter a lot more. I hear the same thing so often from people who say they want to work for themselves–“I would, but I don’t have any good ideas”–and it’s so ridiculous because I’ve had some of the dumbest fucking ideas you could ever imagine.

Consider I once invested in lots of glass. Or that I purchased an acre of a literal swamp on eBay. Or just Google “Bales Ja Morant.”

It’s really, really important to realize that good ideas mean nothing without execution, and bad ideas can become good ideas with the right evolutionary process in place.

In The Secret to Success: Mimic Evolution, I wrote:

Evolution is more or less one giant system of trial-and-error. Nature changes, species adjust. Some traits live and some die off.

The key is that there’s a mechanism for the weakest traits and species to fizzle out. The harsh reality is that’s death. Survival of the fittest.

We see the same thing in some industries, which do a pretty decent job of mimicking evolution, mostly via competition. Take the restaurant business, which is fiercely competitive. Mostly, bad restaurants end up dying off—no one comes to eat—and only the strongest survive. The entire system gains from the process, and the food industry as a whole evolves fairly rapidly.

The faster and more efficient you can make this trial-and-error cycle, whether it’s in your personal life or your business life, the quicker you will find success. Your starting point for truth is way less important than your process for refining and improving your beliefs, especially when you get away from a static worldview and begin to (appropriately) see it dynamically.

Over time, differences in the speed at which you can process information and adapt become exponentially more important than where you begin.

I firmly believe in this idea as it relates to starting and operating a business, even if just as a solo entrepreneur. Come up with some ideas (I’ll discuss some techniques shortly), put them into action, test and iterate, and then adjust.

To give you an example of how this might look in practice, consider two businesses I started in college.

One was a fantasy sports contest that assigned salaries to every player; users had a salary cap to build a lineup, choosing any players they’d like, and the contests ended after just one day. This was like 6-7 years before the first true daily fantasy sports site–an objectively good idea! I even raised a small amount of money and gave away $30,000 in a championship, which was a huge prize at the time.

This idea failed miserably because I had absolutely no clue what I was doing. I didn’t understand marketing. I didn’t understand product. I didn’t understand UI/UX. I didn’t understand pricing. I didn’t understand advertising. I didn’t understand data feeds. I didn’t understand SEO. I also had a blonde mohawk at that time, which didn’t directly contribute to the failure of the company, but I mean c’mon.

That business was actually near breakeven, which in hindsight was a huge signal it was a good idea given how poorly I ran it, but I still shut it down. At that point, I didn’t fully comprehend how to learn and adapt.

The second business–and I use the term “business” lightly here–was an objectively bad idea, but the first one that actually made money. I wrote about it in a recent article, and I’ll call it writing arbitrage:

Basically, internet content was becoming king around that time and there were a bunch of sites that would pay freelance writers decent money to write short (and shit) articles. Remember eHow and About.com and those sites? Stuff like that.

They paid enough that I thought, “Man, this is too much money, I bet people would do it for less.” So they did do it for less, for me. I advertised my own company on Craigslist and Facebook that paid writers very handsomely—and by that I mean about 50% of what I was paid to write through another freelance publishing company at which they couldn’t be accepted—to create short articles, which I’d then publish under my name (with permission, of course…from the writers, not the company).

$25 out, $50 in, and we’re off. I really learned a lot about hiring, marketing, editing, managing a staff, and a variety of other important skills during this time. The best part? I’m not even sure it was technically illegal!

I just remember I was writing and editing a lot of articles like “How to Prune Rose Bushes.” I found interest in the creativity of building a secret stable of ghostwriters, but writing and editing articles about how to build a garden trellis didn’t get me super hard.

My interests at that time were philosophy/theoretical physics, fitness/nutrition, sports analytics…and that’s it. If there was a more jacked amateur physicist working on win probability, I’ve yet to meet him.

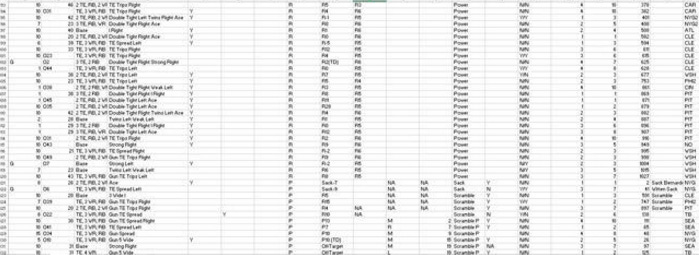

So naturally, I started watching all-22 film and charting Cowboys plays into like 50 categories just for fun–each game took me about 15 hours to complete–then writing about the results.

Here’s a screenshot of a few plays:

Talk about a wild early-20s. Did I mention I’m a complete fucking psychopath? The weird part is despite grinding so hard, none of this ever got me laid.

I had all this data that could theoretically be very useful to the team—and perhaps quite valuable for me—so I made the logical move and emailed the entire thing to everyone in the organization for free. I’m talking everyone: head coach Jason Garrett, Jerry Jones, marketing interns, offensive tackle Marc Colombo, writers, social media managers, event coordinators, sales consultants, a homeless man who slept outside the stadium…everyone.

Anyway, I think the team felt bad for the autistic kid who wouldn’t stop leaving them alone and they gave me a job just to make it all stop. I stayed there a little bit before realizing I’d end up broker than when I was writing about how to care for your hydrangeas.

But really what happened was something called daily fantasy sports came along, which allowed me to apply basically the same analytical process to sports, except for real money. That’s really where I got lucky, as it became clear this was the area in which I needed to focus. It was the perfect blend of my interests and skills: math, sports, writing, and games.

And it was play for me. I got up early and stayed up late playing, writing, and thinking about DFS. I just loved it.

I got my leg in the door the easy way: by simply writing an entire book. I started writing because I could do it quickly and I needed to make money, but for some reason the New York Times let me write for them around this time, mainly about football analytics and the NFL Draft. Even though I wasn’t really an employee, I signed my name like this…

Jonathan Bales

New York Times

…any time I wanted someone to respond to my emails. And that’s what I did when researching how to win at daily fantasy sports; I emailed as many of the top players as I could, telling them I was a New York Times writer publishing a book on DFS strategy. It was technically true.

And that shit worked. These motherfuckers told me everything they knew! Granted, the community was much more open about publicly sharing advice as the industry was so new and growing rapidly, but it led me to a lot of the sharpest minds in the game, one of whom–Peter Jennings, aka CSURAM88–became my business partner.

After briefly building a DFS lineup optimizer that would have failed miserably, we were contacted by a sports betting analytics company called Sports Insights looking to get into DFS. They were extremely engineering-heavy, which is exactly what we needed, and together we founded a company called FantasyLabs, which turned into my first “real” company of note.

I became the CEO of FantasyLabs and learned so, so much during that time. We were immediately profitable, taking on just one investment from Mark Cuban only for strategic reasons. We were acquired by Chernin Group in 2017 in a half-cash/half-stock deal as the largest component of a rollup into a larger media company called Action Network. That company had a large exit in 2021.

Recently, I’ve been back on the grind with a new company called Gambly that builds AI tools for sports bettors. That one is going extremely well–we just sent our 5 millionth bet to sportsbooks this year–which makes me wonder if I’m actually good at starting companies at all or I just got extremely lucky in the highly specific field of sports betting tools and analytics. I guess it doesn’t really matter.

In starting Gambly, I’ve realized how much better prepared I am to be successful compared to before. I’ve learned all sorts of skills over the years–not from theorizing, but from doing–and thought it might be useful for some if I share the most important ideas.

An Outline for Success

This is a general outline I’d use as a starting point for creating a business, being a “solopreneur,” or even for employees looking to progress in their careers. Note that it’s not the only path to success, but just one I retroactively realized has worked for me.

Find Your Area of Focus

The biggest hurdle most people have in starting a business or side hustle is figuring out where to focus.

This is also the most important choice you’ll make, because most ideas are either really bad and not going to work, or just not capable of making much money. Most of your hobbies should just be hobbies.

The place to start, in my experience, is the intersection of your skills and interests. I’ve heard many names for this over the years–cross-pollination, idea sex, skill stacking–but the general concept is that you combine the areas in which you’re naturally talented or have interest. If you’re having trouble figuring out what those areas are, consider the things you do that seem quite easy that others find challenging. For me, one of those areas is writing; I’m not saying I’m some world-class writer, but it seems as though I at least find it quite a bit less challenging than the average fella.

This idea of cross-pollination or skill stacking works out to be a math problem. If you’re top 10% in music knowledge, top 10% in SEO skills, top 10% in writing copy, top 10% in designing landing pages, and top 10% in affiliate marketing, you might not be an elite talent in any particular area, but boy are you going to be able to design landing pages that convert search engine traffic to affiliate leads in the music space.

You’ll be a 1-in-100,000 talent, to be exact, even if you’re just the 90th percentile in each category. And getting to the top 10% in something isn’t particularly difficult, even if you have little experience in that area, because most people are quite bad at everything.

As compared to becoming a world-class talent in any one specific area, it’s much, much easier to become pretty good in a bunch of areas, then combine those skills/interests to find your excellence.

Dominate a Niche

Related to the above idea is dominating a niche. When you combine ideas/skills, you’re basically narrowing down your area of focus until you’re effectively among the best in the world in one niche.

There are a lot of reasons this is important, which I’ve written about this concept in My Extreme Theory of Learning:

In the business world, writer Anthony Bardaro summed up this concept nicely in his article on the future of media: "If you’ve already won with either huge scale or niche focus, you can then try to creep down or up in scale to grow. But, you cannot start in the middle of either spectrum and grow out."

Why is this? There are three primary reasons, in my opinion.

Limited Competition

The first is because there’s less competition in the tails. It doesn’t matter if we’re talking about business or poker or chess, in the game of life, you don’t just want to be the best at what you do, but just as important, you want to be the only person doing it.

Keep redefining what you do—by gravitating toward logical extremes—until you have little or no competition. It’s much easier to move the goalposts and eliminate others from “the game” to reduce competition than it is to contend with everyone and become the top dog in a crowded space. Plus, it’s fragile; in areas in which you’re forced to constantly compete with a shit ton of people rather than innovate, there’s sure to be a lot of turnover at the top. You’re better off playing your own game over taking on the masses at theirs. So extreme learning works because of the 80/20 rule, and it also allows for the (sometimes) unintended advantage of limiting competition.

Bigger Payoffs

The second reason—related to the first—is that if you’re alone in your strategy, you’re more likely to hit on something groundbreaking, and the payoffs for that will be huge. They say you can’t keep doing the same shit and expect different results—that’s the exact quote I think, right?—but you also can’t do what everyone else is doing and expect a sensational outcome. Carving your own path isn’t just more fun; it’s also the best decision for maximizing the rewards you reap when you’re right—and the only one who’s right.

Most Useful Feedback & Faster Learning

The final reason—and the most important as it relates to rapid learning—is that going “extreme” in your decision-making is accompanied by the hidden benefit of gaining more useful feedback on how to adapt. If your starting point for evolution is a logical extreme, you know which direction you need to move should you be wrong. If you’re a writer and unsure on the best length of your writing for whichever goals you have, it’s superior to start writing very short, quick-hitting posts in abundance or go super longform with fewer, more in-depth articles/stories than to be somewhere in the middle. With the latter, it takes longer to adequately adjust to what’s optimal (for whichever goals you have) than with the more extreme approach, which allows for the benefit of obvious adjustments toward a less extreme strategy. And many times, you’ll probably find that working at a logical extreme is the place you want to stay, at least for a period.

It’s much easier to be a big fish in a small pond, and then jump to a bigger pond as you grow, than starting in the deep end. Fish can’t really jump between ponds though I guess, unless the ponds are like super close to each other? But you get the idea.

Become the best in the world in one highly specific area–no matter how niche–and then slowly expand outwards.

Solve Your Own Pain Points

Once you know where to focus, you should go about solving problems you personally have in this area. When we built FantasyLabs, the entire idea was solving my personal problem of quickly creating customizable daily fantasy sports models, and ultimately lineups from that data.

In the Gambly origin story, I wrote about how Gambly began as a chat bot for sports bettors looking to uncover unique bets and perform odds comparisons. The initial idea actually came to my co-founder Cal Spears when he was looking to make a bet on the second tight end off the board in the NFL Draft, but couldn’t find the available bets on sportsbooks.

We decided natural language was the best way to solve this problem we both experienced. That idea is highly specific, but it gave us a springboard to start building other tools sports bettors need that AI is uniquely qualified to solve.

Build Publicly

Talk about what you’re building—struggles and all—as you do it.

I stumbled upon this “hack” accidentally. In writing so much content and so many books over the years, I was indirectly building a customer base for future products. Even though my books did very well for what they were, it’s quite difficult to make a lot of money from writing alone. I think I saw somewhere the median book on Amazon has sub-$1k lifetime sales.

But in writing the books and free content across the internet, I built a base of people who came to trust me in my highly specific area of expertise. So when we launched FantasyLabs, we had a crucial wave of early adopters I had effectively been marketing to for years, unbeknownst to all of us.

The other reason to build publicly is because it opens up a world of future possibilities to find luck. Nearly every person I’ve ever hired has reached out to me, as opposed to me needing to find a convince talent to join, and basically all of them knew of me because of my writing.

Even if you don’t write, create some form of content, even if just on social media, to show others what you’re doing and why you’re a domain expert.

Apply Leverage

Once you find something that works, you want to apply leverage, meaning you need a way to scale.

This is actually an important question to consider early in your journey: if this works, can I reasonably scale it? Effectively, what’s the payoff here if I’m “right” or I “succeed” in creating something of value? What do I win if I win?

The reason I’ve focused on internet companies is that there’s a very high ceiling on potential customers. Whereas a successful restaurant can make only so much money in a year even if it crushes, a successful online subscription service, for example, can scale indefinitely with very little cost of replication. The cost to Gambly for 10,000 customers isn’t much greater than for 10 customers.

Find what can grow, preferably without the need for much additional time/energy/money from you, and then throw fuel on the fire.

Double down when things are working. Create content and products that can live forever. Build for the long haul.

Some Other Lessons I’ve Learned

I really have learned so much, mostly from failing so often, that I could write 100 pages here. Maybe I will do that in a book at some point.

But off the top of my head, here are a few quick-hitting lessons I wish I learned earlier…

There is no “skill” of entrepreneurship or business.

Business isn’t a skill. It’s made up of hundreds or thousands of micro-skills you need to develop along the way.

Communication. Negotiation. Design. Social media. SEO. Email marketing. Whatever…you need to learn how to do many things, and the best way to do that is to…

Learn by doing.

You can theorize about what will work all day long, but there’s no substitute for action. Bad decisions are better than no decision because bad decisions can become good ones, primarily when you…

Iterate.

A plane gets from one destination to another not by perfectly calibrating from takeoff, but from making many small adjustments along the way. Similarly, you’re never going to have perfect vision–not even close–and so it’s more important you learn to make good educated guesses on what will work, then iterate.

Do something. Anything. Gather feedback. Adjust it quickly. Repeat.

Part of your ability to improve this cycle is your willingness to…

Quit early.

You’re going to have lots of bad ideas. Most of your ideas are probably awful. Mine are. Give up on them. Don’t see them through. It’s a waste. For the most part, when an idea is a winner, you know it pretty quickly. Whether it’s a single feature of your business or the entire concept, if it isn’t working early, you shouldn’t actually stick with it unless there are additional signs it will improve.

They say you should quit while you’re ahead, but you should also quit while you’re down only a little (money, time, energy). Quitters win.

And you’ll need to quit a lot, because you should…

Take many chances when the cost is low.

They say the best poker players get the luckiest. This is true in a way, as the best players put themselves in position to benefit from variance the most often.

When the cost is low, you should try many things. Most of them will fail, but you’ll get “luckiest” when you increase your surface area for luck as much as possible. And to help keep costs low…

Don’t raise money.

Some businesses need to raise money, particularly those that benefit from network effects and need to reach a tipping point of usage. But even those are typically better off finding market fit before taking on investors.

There are many reasons you almost certainly shouldn’t raise money:

Stress

Dilution

Needing to answer to others

And with the growth of AI and the ability for very small teams–even a team of one–to now produce at the level of many, there’s simply not the same incentive to raise money as in the past.

And finally…

Motivation is driven by necessity.

The most motivated I’ve ever been in my life was when I had $600 in the bank and moved to New York City because of a girl. A theoretically horrible decision that actually pushed me to figure out how to make money because I was absolutely fucked otherwise.

I also didn’t want the girl to find out I had only $600, which obviously didn’t work since it’s a little hard to live in NYC and hide the fact you only have $600. Want to go to a nice dinner, baby? That’ll only be one-third of my net worth.

Your natural motivation will wax and wane, but you can manufacture it when it’s really needed by making success a necessity. This might mean running a super lean company, publicly committing to shipping something you haven’t yet completed, making a bet on future productivity, or otherwise taking on some form of downside if you fail.

If you forget about the time I sold furbies, and the time I spent all of my money on glass, and the time(s) I gave away all of my high-quality work for free, and the time I bought swampland on eBay, and the time I gave up on literally creating DFS, and the time I pursued ‘magician’ as a career path, I’d say I’m a pretty good businessman.

If you learn anything from me and my failures, it’s to keep firing lots of shots, quit fast when things don’t work, pour fuel on the winners, and remember that every mistake is an opportunity to learn and improve.

So go work on something. Anything. Take on risk. Lose a little. Or a lot. The sooner you do, the sooner you’ll be able to figure out how to win.

Nice to see you back Professor Bales. I always enjoy reading your content. Man it's been 10 years since I first started.

The thing about a lot of entrepreneurs today is that they almost force us to automatically despise them because they pontificate about brain hacks, or business hacks or anything else that's been repackaged from an earlier time and made to look original in today's business climate.

Entrepreneurs also tend to refer themselves as the cringe-worthy "serial" kind (https://youtube.com/shorts/jk1oUiT1qcM?feature=share) which is as annoying as it gets. Not because we assume they can't do what they claim but because they always lead with that claim, as if they have a proprietary Midas touch that turns everything they're connected with to gold.

Essentially they come across as being inextricably exceptional and infallible. You're NOTHING like these people. You show the scars, the scribbles and the waste basket full of attempts and, because of that you're both approachable and likeable and that's thoroughly appreciated.

You seem to understand that blowing your own horn as a first move to attract interest gets you nowhere. That type might ultimately be heard but also resented and despised while doing so. So thanks for not being any of those things Jonathan.